What if You Don’t Agree with a Religious Objection?

the situation

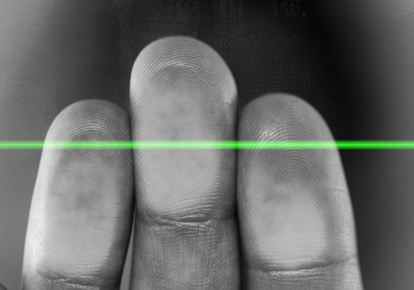

You decide to implement a new time tracking system which involves the use of biometric hand scanners by employees to scan their right hands to clock in or out for a shift. One of your long time employees claims that he cannot use this kind of hand scanner because its use would conflict with his religious beliefs. Can you require him to use it anyway?

the ruling

Maybe not, depending on the nature of his religious objection. Last month, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a lower court’s ruling following a jury finding an employer liable in similar circumstances. EEOC v. Consol Energy, Inc., No. 16-1230 (June 12, 2017).

Beverly Butcher worked as a coal miner at a mine owned by Consol Energy for thirty-seven years with no performance or disciplinary issues. In 2012, Consol put a new time tracking system in place which involved the use of a biometric hand-scanner at the mine to monitor employees’ attendance and work hours (which, up to that point, had been manually tracked by the shift foremen). Butcher, an evangelical Christian, concluded that participating in the hand-scanner system would present a threat to his religious beliefs. Butcher believes that an Antichrist stands for evil and that the Antichrist’s followers are condemned to everlasting punishment. According to Butcher, the Mark of the Beast brands followers of the Antichrist and that the use of the hand-scanning would result in being “marked,” even if there were no physical or visible signs of the scan. He believed that if he utilized the scanner, it would mean his identification with the Antichrist.

When Butcher first raised these concerns, he was told to get a letter from his pastor explaining his need for a religious accommodation. After Butcher provided a letter from his pastor and provided his own written explanation of his objection to the use of the hand scanner, the HR supervisor gave Butcher a letter from the scanner’s manufacturer which was meant to assure him that the scanner did not actually leave any mark on the person using it, including the Mark of the Beast. The letter also stated that the Mark of the Beast is associated only with the right hand, and so Butcher should be able to use his left hand in the scanner. Consol asked Butcher to review this information with his pastor and determine if he still had an objection.

But Butcher maintained his objection on religious grounds. When he communicated this to Consol, he was provided a copy of Consol’s disciplinary procedures related to the scanner, which basically provided that upon four missed scans, an employee would be fired. Butcher retired based upon this. Interestingly, in fact, Consol did allow employees with hand injuries to use an alternate system which just involved entering their personnel numbers on a keypad.

The EEOC brought a lawsuit against Consol, asserting that Consol had violated Title VII by refusing to accommodate Butcher and constructively discharging him. A jury found Consol liable and awarded Butcher $150,000 in compensatory damages and $436,860.74 in front and back pay and lost benefits.

Consol appealed on a number of grounds. One of Consol’s arguments was that it did not fail to reasonably accommodate Butcher’s religious beliefs because there was no actual conflict between his religious beliefs and the requirement that he use the hand scanner. But the Fourth Circuit rejected this argument, finding that this argument is really based upon Consol’s determination that Butcher’s religious beliefs, though sincere, were mistaken. But, the Fourth Circuit explained, “[i]t is not Consol’s place as an employer, nor ours as a court, to question the correctness or even the plausibility of Butcher’s religious understandings.” And clearly, there was another option available that would not impose an undue hardship on Consol because they had permitted two other employees to utilize it. Based on all of this, there was no reason to question the jury’s determination that Consol was liable for a failure to accommodate.

the point

It is important to note that here, Consol was not questioning the sincerity of Butcher’s beliefs. The outcome may have been different if there was any evidence that the objection raised by Butcher was not based on actual beliefs. Instead, Consol was questioning whether this sincere belief was correct—and that is what led to the result here. Employers must be mindful of their obligations under Title VII when it comes to religious accommodations and avoid delving into whether or not they agree with an employee’s interpretations of issues related to his or her religion.